The Crisis and Opportunity in Rare Diseases

.png)

Share

8VC stepped into life sciences to bridge the gap between groundbreaking biomedical innovation and real-world patient care. Our collaborations with visionary scientists have already begun transforming deadly diseases into manageable conditions, and in some cases, outright cures. Despite the immense potential of advanced diagnostics and therapies, however, rare disease medicine remains starkly underdeveloped. At their core, the unmet needs in rare diseases are not only scientific or medical challenges, but fundamental misalignments of commercial and societal incentives.

The "rare disease" label often consigns patients to journeys outside the boundaries of conventional medical care. Too frequently, these patients struggle to even obtain a definitive diagnosis, much less specialized care or targeted treatments. Many rare diseases are genetic, and predominantly afflict children from birth. Recent breakthroughs in biology and genetic medicine have radically transformed what's possible, turning previously hopeless cases into actionable opportunities. Despite scientific progress and considerable resource commitment, these initiatives too often falter in transitioning from clinical trials to reaching patients in need.

Why? Large pharmas, constrained by the myopic search for the next blockbuster drug (i.e. Ozempic), hesitate to advance therapies tailored for small patient populations. For a pharma, small patient populations mean small profits, and these patients are left behind. This hesitation halts innovation precisely at the moment it should accelerate, underscoring the urgent need for novel business approaches and entrepreneurial vision to shepherd life-changing therapies from bench to bedside.

Historically, biotech financing has been dominated by specialized venture investors focused on flipping companies to big pharma via acquisitions, sidesteping the hard work of getting new drugs to patients post-approval. Big pharma, however, overwhelmingly prioritizes drugs with large patient populations and steady reimbursement potential. Consequently, rare, particularly ultra-rare diseases often struggle to attract sufficient investment given their small patient populations and high likelihood of one-time cures.

Over the past two decades, the rare and ultra-rare disease landscape has undergone a structural shift driven by three converging forces: dramatically improved disease identification, the maturation of genetic medicine as a therapeutic modality, and increasingly supportive regulatory frameworks. Advances in whole-genome sequencing, biomarker discovery, and population-level screening have sharply expanded both the number of recognized rare diseases and their diagnosed prevalence, while simultaneously defining clear molecular targets for intervention. Concurrently, novel genetic and cell-based therapies now make it technically feasible to directly correct, replace, or silence disease-causing genes in ways that traditional small molecules and biologics cannot. Finally, regulators have responded to this scientific inflection by modernizing approval pathways, incentivizing orphan drug development, and embracing biomarker-driven trials, substantially reducing time to market. Together, these dynamics create a uniquely favorable moment: previously intractable genetic diseases are becoming both diagnosable, and druggable at scale.

The Ultra-Rare Challenge

Ultra Rare and Orphan Diseases

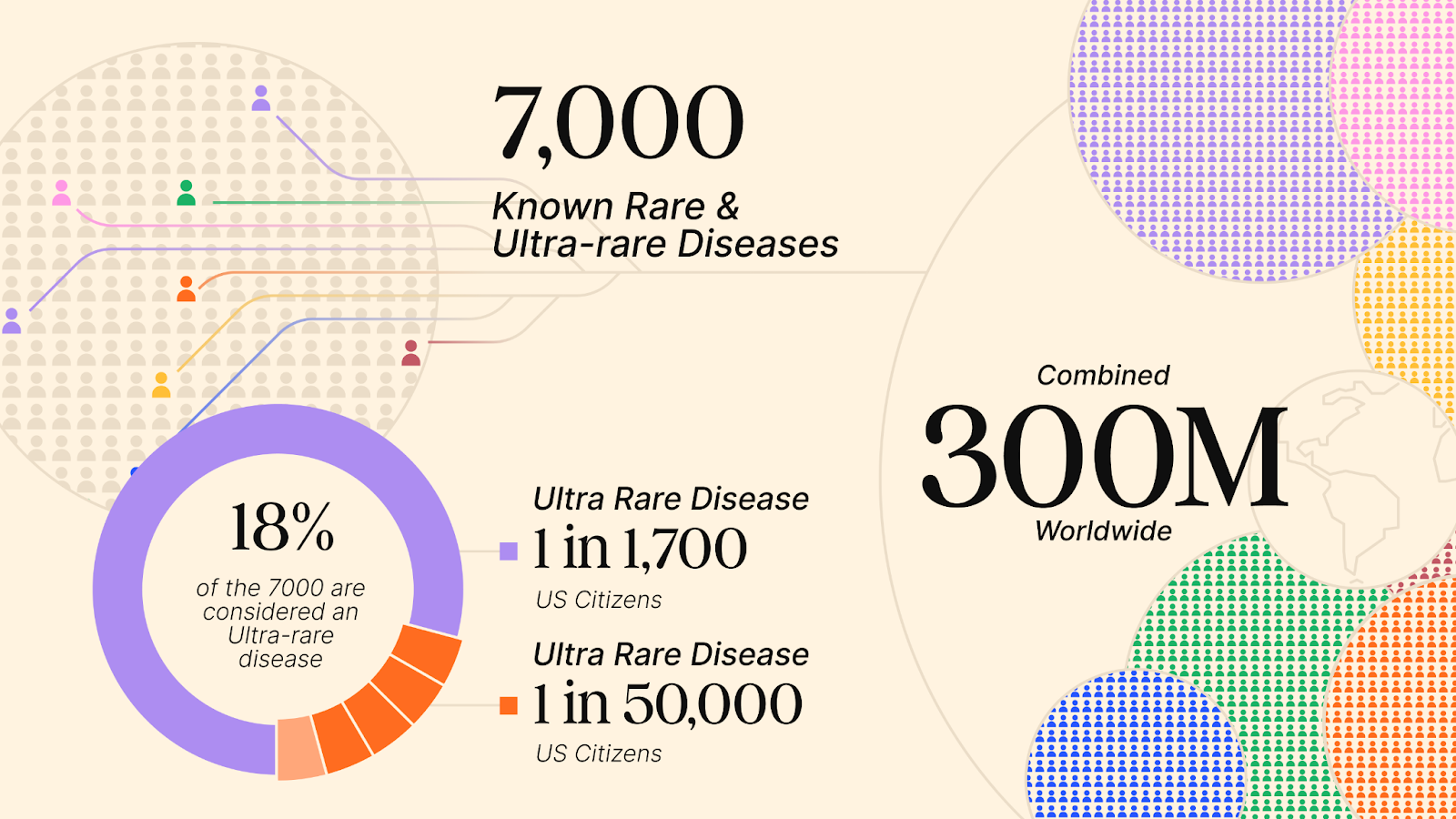

Diseases with fewer than 200,000 U.S. patients are considered “rare”, while “ultra-rare” diseases typically affect even fewer, with a prevalence of fewer than 1 in 50,000 (or under ~6,700 U.S. patients)1. Over 7,000 rare and ultra-rare diseases are known today, and that number continues to grow as novel diagnostic methods evolve. Yet these diseases are anything but rare, collectively affecting 25 million people in the U.S. and 300 million globally.

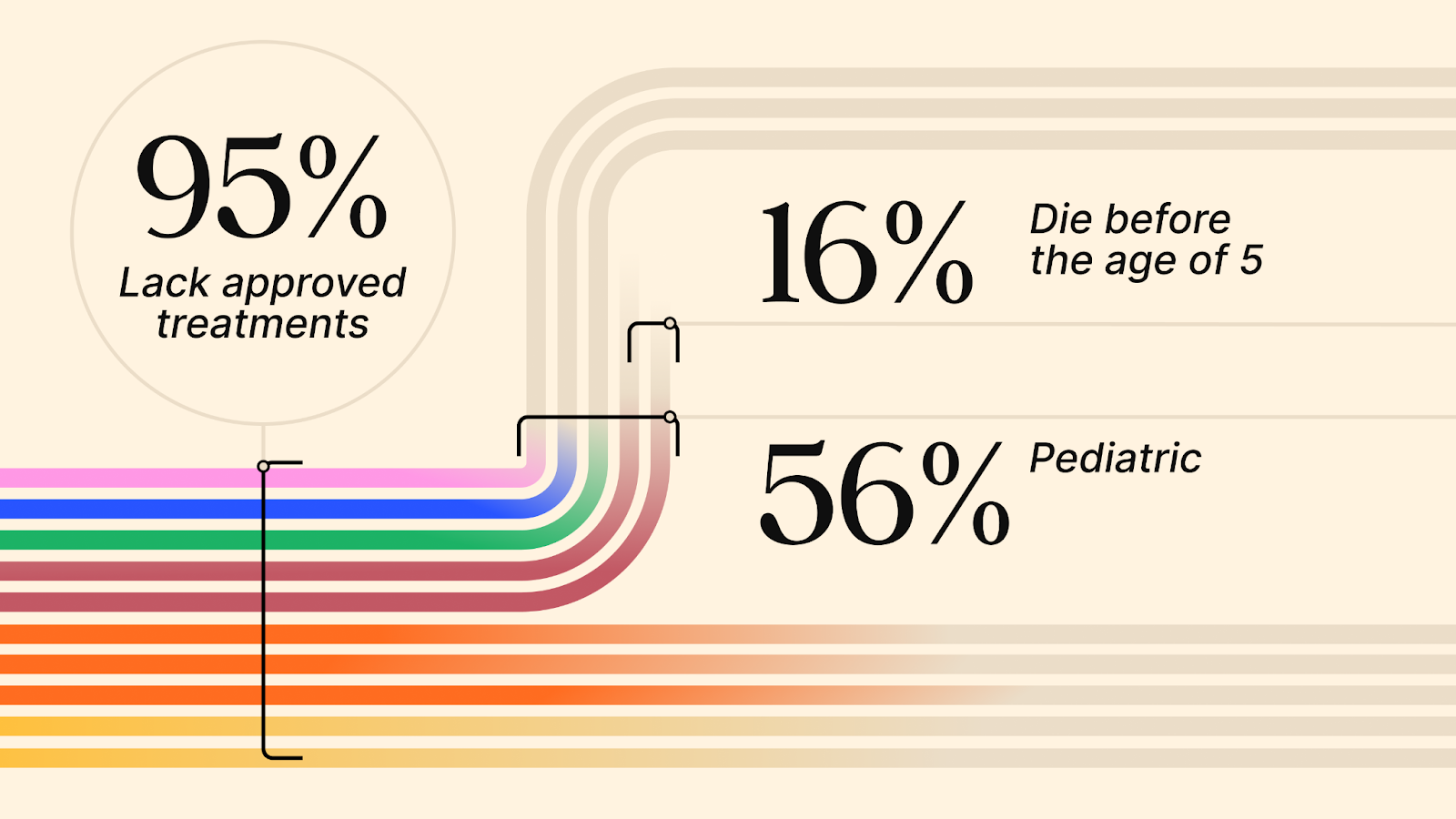

The Lancet2 reveals a grim reality: “Around 80% of rare diseases have a genetic cause, almost 70% of which present in childhood; about 95% lack approved treatments; the average time for an accurate diagnosis is 4.8 years; and about 30% of children with a rare disease die before age 5.”

Orphan diseases are defined as those without traditional commercial support from R&D-focused companies. They tend to be synonymous with rare diseases because their market sizes and available reimbursement preclude outside investment.

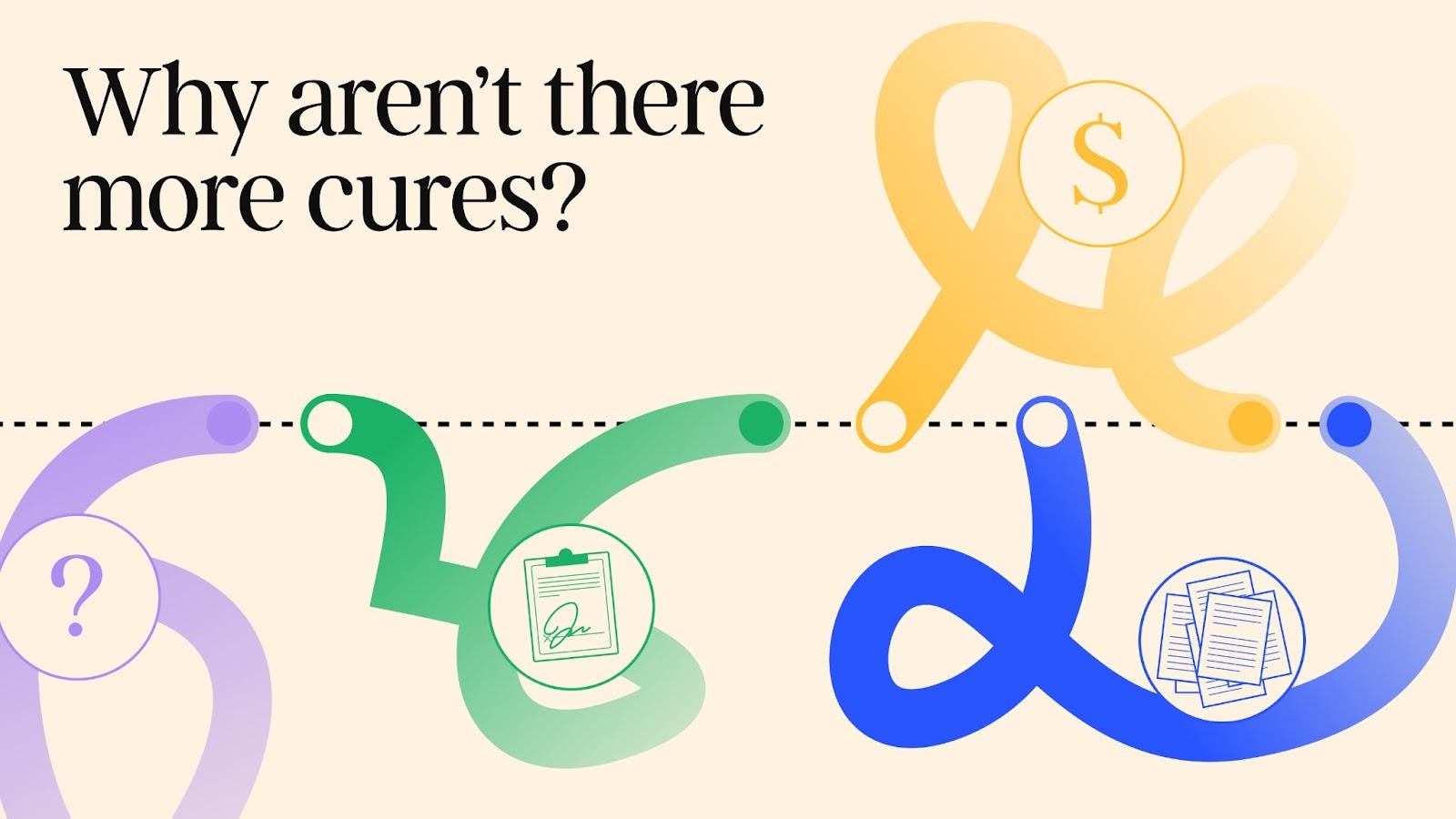

Historically, several factors have made ultra-rare diseases extremely challenging:

- Discovery: Discovery of rare diseases requires coordination between physicians and scientists. The default for ultra-rare disease patients is to die without knowing what caused their illness. In larger indications, academic medical centers that merge research and treatment can work to discover the underlying causes, but smaller facilities don’t have this option. A child might die in a rural or community hospital without anyone understanding why.

- Diagnosis: Due to the low prevalence of these diseases, the rate of diagnosis is extremely small, even when diagnostics exist. The U.S. Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), a list of disorders recommended by the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services for inclusion in state newborn screening programs, only contains 64 conditions3, even though whole genome sequencing can detect the vast majority of rare diseases.

- Trials: Recruiting patients to run clinical trials can be so time-consuming as to starve out companies, and it is prohibitively difficult (if not unethical) to run a standard well-powered placebo-controlled trial.

- TAM: Small patient populations by definition mean few customers. Pioneering groups like Genzyme charged high prices to make the market investable. This still requires considerable work to get appropriate reimbursement whenever a new drug is approved.

- Curative Business Model: The current reimbursement model for diseases is reactionary, and focused on “treating”, not “curing.” A lifelong patient treatment regimen means repeatable cashflows, whereas each cure effectively shrinks TAM. To counter this, drug developers must charge higher prices up front. Such “one-time payment” (OTP) business models have had difficulty taking hold in our payer system.

Despite these challenges, there are many scientific, regulatory, and payer initiatives that have expanded our ability to address these diseases. The major outstanding issue is a market dislocation, due to big pharma disinterest and the way biotechs are currently funded.

Pharma, Biotech, and VC

Biotech companies rarely commercialize their own drugs due to extremely long and costly development timelines. In the U.S., developing a drug from research to FDA approval typically takes 12-15 years4. Instead, the dominant model of biotech startups is to focus on R&D until achieving clinical proof-of-concept (POC) and getting acquired by big pharmas, which already enjoy strong commercial engines and low cost-of-capital for large drug launches. This dynamic forces biotech to cater to big pharma needs.

Big pharma stocks are valued on cashflow and pipeline potential. Cashflow for each drug product drops off precipitously after a branded drug’s patent life expires, at which point pharma regularly sees product line revenues drop by up to 95% (less for advanced biologics). When these organizations are focused on plugging $1-10B+ revenue gaps in their pipelines, they cannot launch products with peak sales potentials far under $1B (and increasingly $2B or $3B). Additionally, their operational expertise concentrates on development and commercialization, not early discovery research. As a result, pharma seeks to consistently replenish therapeutic products with programs with “blockbuster” potential, via biotech M&A.

Traditional life science VC fits this equation by building and financing biotech aimed at pharma acquisition. Given high costs to exit, with capped upsides due to pharma budgets, life science funds need to focus investment on low loss ratios and fast distributions to paid-in capital (DPI) to achieve competitive (internal rate of return) IRR to other funds. These funds do *not* aim to invest in enduring companies that compound growth, which would require revenues and profits. This dynamic keeps them keenly attuned to pharma M&A, causing both traditional funds and subsequently funded biotechs to focus on five-year time windows.

Unmet Need

Pressures resulting from the interplay between biotech, pharma, and life science VCs dis-incentivize biotech companies from developing drugs in “small markets” like ultra-rare diseases, despite the advantages of known target biology and fast time to market.

This is a classic innovator’s dilemma for tech companies as well. If Magnificent 7 companies attempted a product with “only” $200mm in revenue, it would also be shuttered. Instead, startups can pursue these small, valuable areas until reaching scale. Any SaaS investor would jump at a company with $200mm in revenue at 95% gross profit margins. Unfortunately, since biotech companies are built for acquisition, such outcomes are simply not in M&A scope. Thus, despite massive unmet patient need and generational opportunities for cures, there is a dearth of development.

Why Now

Improvements in Identifying, Screening, and Diagnosing Ultra Rare Diseases

Over the past 20 years, advances in whole-genome sequencing have dramatically improved detection and identification of rare mutations in patients. By combining these sequences with electronic healthcare records and informatics techniques, scientists have found numerous new pathogenic gene variants, increasing both the number of known rare diseases and our depth of understanding. Biomarker discoveries that have spurred therapeutic innovation include:

- Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD): The 2004 discovery of the aquaporin-4 IgG antibody as a specific marker for NMO transformed diagnosis, leading to recent FDA-approved therapies specifically for AQP4-positive NMOSD5.

- Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis: This autoimmune encephalitis was previously unrecognized (many patients were thought to have idiopathic psychosis or viral encephalitis). A blood/cerebrospinal fluid assay for anti-NMDA receptor antibodies now allows for definitive diagnosis.

- Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM): Around 2016, a novel nuclear medicine scan (bone scintigraphy) was found to detect ATTR cardiac amyloid noninvasively, leading to a surge in diagnoses. Improved detection not only increased prevalence numbers, but also created a new therapeutic market, exemplified by the 2019 approval of tafamidis (the first medication for ATTR-CM)6 and the 2024 approval of Acoramidis.

Better sequencing tools and other assays have also increased the detected prevalence of genetic diseases. The Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) was initially proposed in 2005 and implemented in 2010 to screen for genetic diseases for newborns, causing 5x-60x spikes in known prevalence of genetic diseases.

Novel Therapeutic Modalities for Genetic Medicine

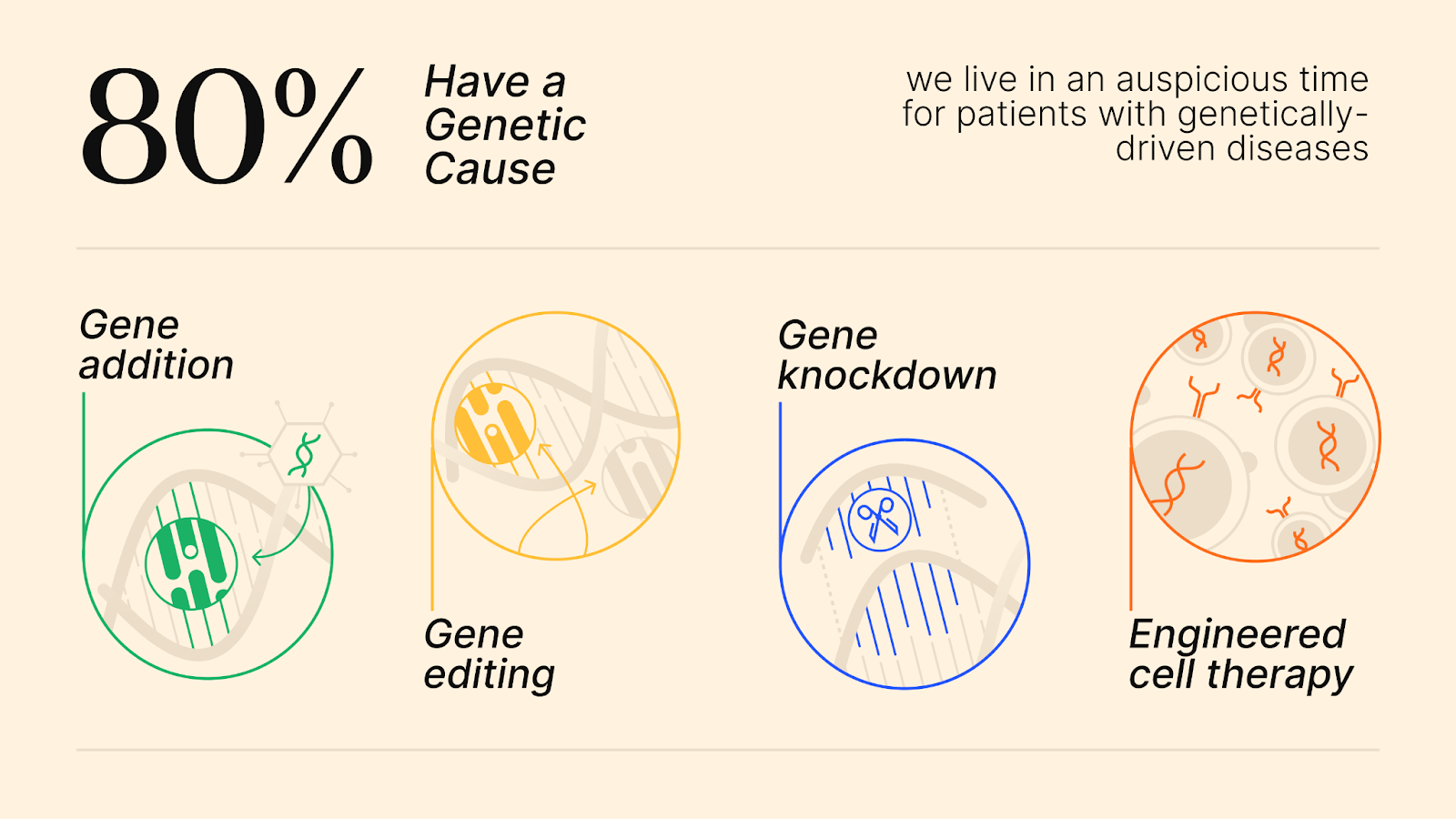

Rare and ultra-rare diseases are primarily caused by single faulty genes, meaning we know exactly what to do to fix them. How to apply the desired fix is the entire challenge. Traditional modalities like small molecules and protein biologics cannot be curative, since they cannot ever completely recapitulate the normal results of a faulty gene.

Fortunately, we live in an auspicious time for patients with genetically-driven diseases. After decades of hard work and research, genetic medicines that can directly modulate genetic function are available.

- Gene addition: This approach uses a “vehicle” called a vector to deliver a healthy copy of the afflicted gene to a patient’s cells to restore proper expression of the missing or mutant protein. Opportunity: Thousands of these delivery vehicles and genetic payloads were developed and characterized in recent decades during the AAV gene therapy boom, but only a few ever advanced to the clinic.

- Gene editing: This technology corrects the underlying mutation in a patient’s cells that causes the disease. Opportunity: The advent of CRISPR spurred innovation in this field, creating tools and algorithms to correct nearly all mutations, but current drug approval is not designed to accommodate this type of precision medicine.

- Gene knockdown (knockout): Some rare diseases are caused by mutations that actually have a toxic effect on the patient’s cells. Opportunity: There are validated tools to knock down/knock out formulations for every gene in the human genome.

- Engineered cell therapy: First approved in 20177, this therapy takes T-cells out of a patient’s body and engineers them to kill target cancer cells. Now this mechanism is being expanded to auto-immune diseases.

This proliferation of novel mechanisms means such an approach to genetic medicines is only newly possible.

Regulatory Tailwinds for Orphan Diseases

Recognizing the unique challenges of rare diseases, the FDA has been refreshingly forward-thinking in exploring programs to reduce time to approval and commercialization. In the last five years, Peter Marks, ex-head of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) has been vocal in re-orienting public perception and the FDA’s mission to recognize the genetic revolution, and accelerate the approval of many new drugs for genetically driven diseases8,9. Salient programs include FDA Rare Disease Guidance (2023)10, FDA Rare Disease Innovation Hub (2024)11, START Pilot Program (2024)12, and Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC) (2021)13.

Historically, Congress, the FDA, and patient advocates have continuously reformed the FDA to orient regulatory and economic incentives around patients, rather than against them. Programs enacted over the years include Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher (PRV)14, which incentivizes development of therapies for serious, rare pediatric conditions by awarding transferable vouchers for priority FDA review. These vouchers shorten the FDA’s review of a future application to 6 months. Today’s market rates for these vouchers range between $100mm-$200mm and amount to a prize for developing a new rare pediatric drug. As recently as January 2026, Jazz executed an agreement to sell the PRV from the FDA approval of the targeted brain cancer medicine Modeyso for $200mm15. Another important initiative is the Orphan Drug Act (ODA)16, which offers 7-year U.S. market exclusivity, fee waivers, and tax credits for rare disease drugs.

Finally, research discoveries in biomarkers are also being incorporated into more efficient clinical development. Given that these diseases might take years to show clinical manifestations, the FDA has been open to trials that demonstrate improvement in causal biomarkers, vs classical hard clinical endpoints. This can greatly shorten timelines to readouts enabling approval and consequent patient access. The NIH and ARPA-H are throwing their weight behind projects to expand the utility of novel biomarkers for rare diseases, creating additional pathways for trials.

Summary

In the past ten years, progress in science, technology, and regulation has made it much easier to develop treatments for rare diseases. New tools like genome sequencing and advanced diagnostics have helped doctors better identify rare conditions, while cutting-edge therapies such as gene editing and engineered cell treatments can now target the root causes of many of these diseases. At the same time, the FDA has created programs to speed up drug approval and reward companies that develop treatments for rare conditions, especially in children. Although many promising drug programs were paused during the recent biotech downturn, they still exist and could be restarted or licensed at a low cost. This has created a rare opportunity for investors and companies to pick up high-quality assets cheaply. Past success stories like Genzyme and Alexion show that with the right science and strategy, rare disease drugs can become billion-dollar businesses.

References

1. Orphanet. https://www.orpha.net/.

8. Gottlieb, S. Remarks on FDA’s Role in Advancing a Modern Framework for Gene Therapy. (2017).

9. Marks, P. FDA’s Efforts to Facilitate the Development of Cell and Gene Therapies. (2022).

16. Herder, M. What Is the Purpose of the Orphan Drug Act? PLOS Med. 14, e1002191 (2017).

.jpg)

.png)